Managing Liquidity and Credit Migration in a Time of Crisis

The breakneck speed of central bank tightening after a decade of low interest rates has uncovered risks that remain in the financial sector post the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008. As the dust begins to settle, regulators will look to address any areas of perceived supervisory weakness exposed by the collapses of SVB, Signature Bank, First Republic Bank and Credit Suisse, a bank of systemic importance. For depositors and investors, the safety and the liquidity of their cash is therefore at the forefront of minds having received a very public lesson on the benefits of diversifying credit exposure and thinking carefully about the security and liquidity of true operating corporate cash balances. Understanding bank liquidity and credit – in aggregate and or individual banks - is key to reducing credit and liquidity risk, but few corporate treasury functions are sufficiently resourced with which to undertake the fundamental analysis necessary to distinguish between the relative credit worthiness of top tier bank credits.

This paper looks at the impact of March’s banking crisis on liquidity and credit risk, especially bank credit which typically forms a large proportion of the holdings of a money market fund, and compares the current crisis to previous crises of the last 15 years.

A Liquidity Crisis

The GFC witnessed a number of challenges for money market funds, with widespread support provided by sponsors and the failure of the Reserve Primary Fund in the US. As a result, regulators in a number of markets including Europe and the US worked with the money market fund industry to create frameworks that aimed to help prevent the types of issues seen in 2008. In 2020, as the COVID-19 crisis caused major disruption to financial markets around the world, these frameworks were found to work broadly as designed, ensuring funds were resilient and able to fulfill their obligations to investors. However, the extreme market volatility did not pass entirely without challenge for the industry. Three Prime Funds in the US required some support from their sponsors (which is not permitted in Europe), albeit on a small scale, and there was significant government intervention in the US in the underlying Treasury market.

Since 2020, the money market fund industry has withstood periods of market stress, first, a period of ultra-low interest rates following extraordinary intervention by central banks to provide market liquidity during the Covid-19 crisis. Next, as central banks globally, almost without exception, grappled to constrain rising inflation in March 2022, that extended nadir in rates was flipped on its head as central banks unleashed the fastest rise in interest rates for three decades. Money market funds have experienced record inflows in this period, as investors sought cash investment solutions offering high levels of credit diversification and liquidity during a period of market turbulence that also respond quickly to reflect the hikes in policy rates.

In the face of these challenging conditions, liquidity in the market broadly held up in 2023, and there was no market dislocation on the scale seen in 2020. As one of the foremost instruments used by money market funds, the largest risk-free asset class, and one of the most liquid, the US treasury market liquidity is of paramount importance across the broader market and the focus of this section. Despite fears, the treasury market did not gum up as it has in the past, but it did not function entirely smoothly, especially considering how limited the eventual scale of the bank failures turned out to be.

Ever since 2020, there has been widespread recognition that the treasury market has been under increasing stress, most visible in the steadily widening bid-ask spreads since the Covid-induced market panic. The tensions that have built in the system were exacerbated by the move from extreme quantative easing to a sharp hike in interest rates across the western world. In March 2023, this sudden rise in interest rates exposed vulnerabilities in some bank balance sheets; large, unrealised losses on unhedged bond portfolios purchased by some US regional banks during the period of ultra low rates spooked depositors. Several banks broke under the pressure from depositor withdrawals before governments had to step in; Signature bank, Silicon Valley bank (SVB), Credit Suisse and First Republic all buckled under pressure from customer outflows.

During this period, especially during the first week following SVB’s collapse, the market in treasuries quickly reacted. Volatility in the treasury market rose sharply, bid-ask spreads jumped (particularly for the less liquid off-the-run secutiries) and record trading volumes were documented. On one day during the week following SVB’s collapse, $1.5trillion dollars of treasuries were traded on the market, in a $22trillion dollar asset class. In part this was also due to a sharp realignment of rate expectations as investors priced in an increased likelihood that rates would not reach the previously predicted heights, and would peak sooner, alongside the usual investors engaged in a flight-to-safety and those selling their liquid assets to obtain liquidity. Trading volumes proceeded to decline over the next few weeks, with bid-ask spreads and volatility following. The market did not collapse and only indirect intervention was required to ensure the smooth functioning of the market.

2008 played host to significantly worse market disruption, a greater need for liquidity, and a much larger flight-to-safety response from market participants - and the treasury market on several different metrics was not as badly stressed as 2020 and 2023, twice in two years. Key to understanding the current instability is to understand how the market has changed to become more fragile. The first change, and the most important, comes in the changing role of the primary dealers, large banks who acted as backstops in the market. After the GFC, regulations forced banks to hold capital against treasuries, as part of the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) covering various on- and off-balance sheet assets and exposures. This effectively limited the ability of the primary dealers to intervene in times of market stress. From 2008 to 2022, their proportion of traded treasuries fell from 14% to 2%. The hedge-funds, high frequency traders, and other institutional investors are not suitable to fulfil that role; indeed, large leveraged bets from some of these market participants can exacerbate these very same liquidity events.

On the flip side, the US government’s deficit’s has grown, and has continued to outpace the already constrained primary dealers’ ability to absorb extra treasuries. The withdrawal of quantitative easing in late 2022 has exacerbated this issue, as the largest purchaser of government paper has withdrawn from the market. Together, greater supply and a more limited ability to meet this has led to a systemically more fragmented and fragile market.

Despite this wider market fragility, intervention was more muted during 2023 compared with 2008 and 2020. This reflects the smaller and more contained nature of the crisis, which was limited to a handful of bankruptcies. While several other banks have experienced elevated outflows, government deposit guarantees and fresh liquidity injections to support the banking sector largely mollified concerns among both depositors and investors of contagion beyond the smaller regional US banks or indeed among banks outside of the US. Central banks have apprecieated the importance of properly functioning money markets during a crisis, and lent funds, in the words of Walter Bagehot in 1873, one of the first to enunciate how to respond to a bank run, ‘as largely as the public ask for them’.

However, two important, though more subtle moves helped ensure sufficient liquidity in the market in 2023. Unlike in 2020, there was no suspension of the SLR rule for treasuries nor a large bond purchase scheme, and no need for it. The first, and most important, was a change to the Federal Reserve’s discount window to price treasuries held as collateral at par, rather than according to market price. For those banks with large, unhedged exposures to low-yielding treasuries that could not be sold without crystalising losses, this provided a lifeline. Use of this facility increased over thirty times from before and after SVB collapsed. Secondly, the standing repo facility, instituted in 2021, was utilised for the first time during a market crisis and helped provide the ‘smooth market functioning’ it was designed to uphold. This facility allows the Federal Reserve to transmit it’s monetary policy by setting a minimum dollar interest rate on overnight lending beyond a banking sector whose role as the main lender of funds in the economy is steadily declining. The repo facility, which was used by non-bank financial institutions and money market funds throughout the crisis, complements the Interest on Reserve Balance (IORB) facility that the Federal Reserve provides for banks.

Further changes to the treasury market are expected, following the approach of the Inter-Agency Working Group on Treasury Market Surveillance’s (IAWG) evolving plan. They have two main proposals: first, through a variety of measures, to obtain a more granular, more comprehensive, and faster understanding of what is happening in the treasury market with better data. Secondly, they are seeking to institute a central clearing house for treasuries, replacing the primary dealers. This would have the added benefits of guaranteeing counterparties and forcing all market participants to hold collateral, limiting the impact positions being unwound during market shocks. These are longer-term projects that are likely to be completed over several years, so the current structure of the treasury market remains important to understand.The effects of different regulatory regimes are becoming clear. US regional banks with a balance sheet size below a defined threshold, for instance, are exempt from some regulatory requirements, such as regular stress testing, that their larger peers are subject to. US regional banks formed the epicenter of the crisis. Meanwhile, EU and UK banks have been held to more stringent regulatory requirements and have remained largely insulated from the turmoil. UK and EU central banks had been less liberal with their support for financials in 2020 than their American counterparts; their resolve has not needed to be tested.

In a mirror image of the 2020 crisis, the financial industry has shown the first signs of weakness while the corporate sector has remained in a relatively strong position. This reflects the nature of the crisis – a lack of liquidity among a small number of banks in the face of sustained deposit withdrawal activity. Once contained, there exists little reason to spread to the wider corporate sector immediately.

Indeed, corporates remain in a generally solid financial position, with corporate profits as a proportion of GDP still at elevated levels relative to historical levels, and debt financed at attractive rates during Covid-19. Spending across the consumer economy is strong and unemployment at historic lows. Bank lending remains healthy, with no indication of a sharp rise in loan loss reserves. However, these are all lagging indicators, and the events of March may yet have their impact felt throughout the real economy as banks tighten access to credit as part of a reexamination of risks and macroeconomic condtions.

Given the limited number and scale of bank failures in 2023, as well as the muted impact this has had immediately on the broader economy, it is not surpirising that the market continued to function. While the success of interventions to underpin the stability of the banking sector belies the uncertainty in the market during the first days of the crisis, in retrospect we can appreciate that it would have been a stark failure had there been a more serious liquidity crisis in March 2023. Interventions on the part of the IAWG and others will take time to implement, and in the meantime the market liquidity’s structural fragility remains a source of concern. Should more difficult economic conditions begin to emerge towards the end of 2023, it is not difficult to imagine a second real-life liquidity stress test taking place.

HSBC focus on Liquidity

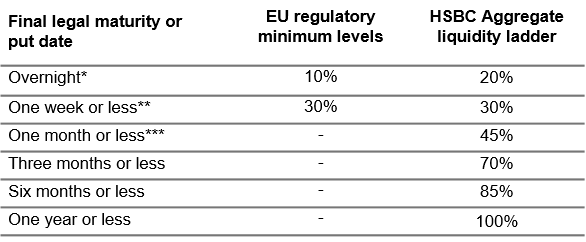

We have always focused strongly on the provision of liquidity in the HSBC Global Liquidity Fund (GLF) range and for example have historically made a number of enhancements to our Liquidity Investment Guidelines that go beyond the overnight and one week liquidity limits introduced in European money market fund regulations.

1. HSBC GLF Liquidity Profile

Source: HSBC Asset Management

The first focus area of our guidelines is direct liquidity in the fund where HSBC target an overnight position of 20%, rather than the minimum 10% defined in the regulations. In the recent crisis this made meeting any initial redemptions less challenging. However, in a prolonged crisis it is important to adapt these targets to the new environment so as to reduce the need to liquidate securities during any extended period of redemptions. To achieve this, minimum holdings for various maturity buckets have always been defined (Table 1) to ensure that our Liquidity funds are well positioned to withstand sudden changes in market liquidity and/or our MMF investors' liquidity demands. During periods of market stress, as has happened frequently since 2020, we have increased our overnight and weekly liquidity target levels. During the peak of the 2020 and 2023 market crisises we raised these to 30% and 50% respectively, levels which afterwards were adapted on a market by market basis, as and where liquidity has improved.

The second focus area, and as important, is setting client concentration limits. Our guidelines target a maximum 5% of AUM invested by an individual client. MMF regulation in the US and Europe is silent on such liquidity risk controls and only reference regulation on knowing your customer. During the GFC much of the pressure on money market funds came from particular client sectors with a tendency towards larger redemptions. The most obvious were some types of multi-national corporates that withdrew balances on a large scale to meet cash flow needs or to reposition cash balances. However, more problematic, and the root cause of some significant fund bailouts in the GFC, were hedge fund and securities lending cash collateral clients that withdrew balances on an even larger scale. Looking at client behaviour during the recent Covid-19 crisis we can see a similar pattern of redemptions, with some withdrawals from a number of multi-nationals corporates, especially some with US headquarters, and some large redemptions from securities lenders. Our robust client concentration limits and liquidity management framework ensured these withdrawals were manageable. This was most noticeable in 2022, following the LDI crisis, when our funds suffered one of the lowest levels of deviation from a net asset value (NAV) of £1 and one of the least levels of assets under management volatility among our peers as a result of managed client sector concentrations. Funds with high concentrations of clients in the UK pension industry suffered from highly volatile flows and a significant deviation of the fund NAV.

One of the reasons that HSBC has always sought a AAAmf rating from Moody’s is the requirement to manage to particular client concentration limits. This reinforces our view on the importance of this area of liquidity risk management.

Assessment of a fund’s liquidity is based on the ratio of overnight liquidity to the amount of equity owned by the three largest investors in the fund

Source: Moody’s Investor Service MMF Ratings Methodology – January 2019

Individual client concentration is an under-appreciated area where risk needs to be managed, but it is the client sector concentration that can be more problematic in times of market stress. Fund Management companies need to have a deep understanding of their client base and take prudent steps to manage the risk around client segment concentration as this concentration has been a key driver of redemption during crisises. For these reasons we also utilise client sector concentration guidelines, as well as individual client concentration limits, allowing no more than a combined 20% exposure from Hedge Funds and Securities Lending clients.

We always seek to apply the lessons learned from periods of market stress, and following that in 2023 we have identified two areas to improve our liquidity risk management framework. Firstly, we have enhanced our liquidity profile analysis with our client base to ensure we better understand behaviour, particularly in times of market stress. Secondly, we are investigating the liquidity of various currencies and the potential need to have liquidity ladders appropriate to the currency.

Credit focus

As recent issues regarding liquidity become less acute, we need to anticipate whether a liquidity crisis could become a full blown credit crisis, the current perception of credit risk and how the possible downward migration of credit ratings might impact a money market fund investment strategy.

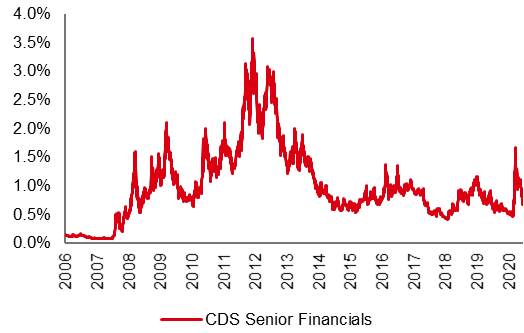

2. Credit Default Swaps for financials

Credit Default Swaps allow investors to offset the risk of a default from particular debt issuers and therefore the level directly reflects concerns of default. Chart 2 shows a basket of senior financial issuers and the cost of the Credit Default Swap. This chart demonstrates that not only are concerns regarding financials defaulting less than during the GFC in 2008 but are also less than during the European Debt crisis in 2011 and the Covid crisis in 2020. The levels of CDS for single issuers could rise sharply, as with Credit Suisse in March 2023, but in aggregate the market has not seen large changes in CDS levels. The market has seen little risk of further credit events occurring across the financial markets, and judged the events in the US and Switzerland unique cases.

The fact that bank credit has performed much better during the recent crisis to date should not, on reflection, come as a great surprise. The changes to banking regulations since 2008 have been significant, ranging from the creation of ring-fenced banks and bail-in securities to the reduction and restructuring of balance sheets, and the introduction of stress tests by central banks. These measures have been tested this time round, most notably the bail-in securities like AT1 debt, which provided much-needed capital for Credit Suisse, despite some investors’ expectations. Quiescence in the market in part also reflects the fact that governments and regulators have been keen to ensure that banks are provided with sufficient liquidity to stave off runs. Questions have been raised regarding the relatively less stringent regulatory regime US regional banks have been held to versus the larger global banks. However, contagion from the collapse of those smaller banks has been limited. In short, despite continued jitters around the sector, banks are still significantly better positioned than in 2008.

In contrast to the Covid-19 crisis in 2020, when corporates were also in a challenging position and banks were relatively stable, in 2023 it is the corporate issuers who are in a better position. Their credit spreads have risen minimally, and stock prices have been unaffected. Instead, for corporates there remain headwinds going into the second half of 2023, including over persistent inflation, slowing growth (including in China), and rising unemployment. Indeed, the latest volatility in the banking sector is expected to negatively impact the real economy, through transmission mechanisms like more limited access to credit. Where concerns regarding non-performing loans from Covid were dispelled due to the extended bull market in 2021 and continued economic vitality into 2022 (despite stock market declines), less positive economic indicators for 2023 suggests caution going into the latter half of the year.

It must be remembered that although certain corporate issuers may represent excellent long term relative value, the volatility of these issuers can have significant impacts on the mark-to-market valuation of money market funds that could ultimately result in pressure on shadow net asset values.

Bank Credit Default Concerns

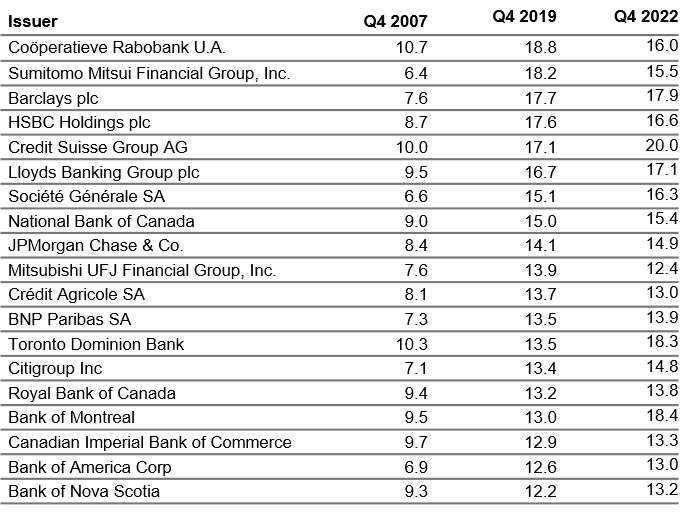

As of end March 2023, the majority of banks have had their credit rating affirmed by S&P and Moody’s, and in general the global banking industry remain a high single A rated sector. However as we progress through 2023 the outlook becomes less certain. In most countries, concerns around the real economy as we come to the end of the credit cycle mean that banks are particularly mindful of non-performing loans on their books.3. Bank Tier 1 Capital Ratio

Source: Bloomberg, HSBC Asset Management

Though we should be mindful not to focus on fighting the last financial crisis, as the source of risk that sparks the next one will almost invariably arise from somewhere else, it is worth examining the home loan market. During the GFC it was the secured mortgage loans that put the banks under significant stress as delinquencies increased significantly. In 2023, the current crisis has yet to impact the real economy and may not reach it. If and when it comes, the resulting impact on unemployment is of particular importance for banks as this is a strong indicator for delinquencies. However, mortgage origination processes have been strengthened markedly since 2008 which should mean that any issues should not be on the scale of the GFC. Corporate real estate has been suggested as a source of risk, stemming from changing working and living arrangements post-Covid; this is an area our credit teams are examining closely.

One thing we can be certain of is that banks are better capitalised than ever (as is evident from Table 3). Ultimately the ratings agencies focus on one thing; the ability of a bank to absorb losses. When looking at the types of banks that are approved for investment in the HSBC GLF range they are typically large, systemically important banks with varied and diverse loan books and depositor bases, and capital ratios well above the minimum regulatory requirements. Investors should have a high degree of confidence holding short dated debt instruments issued by high quality top tier banks as we do not have concerns about defaults of these types of banks, or any bank that is currently approved for investment. As already discussed the current levels of Credit Default Swaps clearly demonstrates how much cheaper it is now to protect against bank default than it was just a few months ago.

As we navigate the rest of 2023 and look beyond into 2024 it is not defaults that have the potential to cause problems for investors in bank debt but the possibility of downgrades.

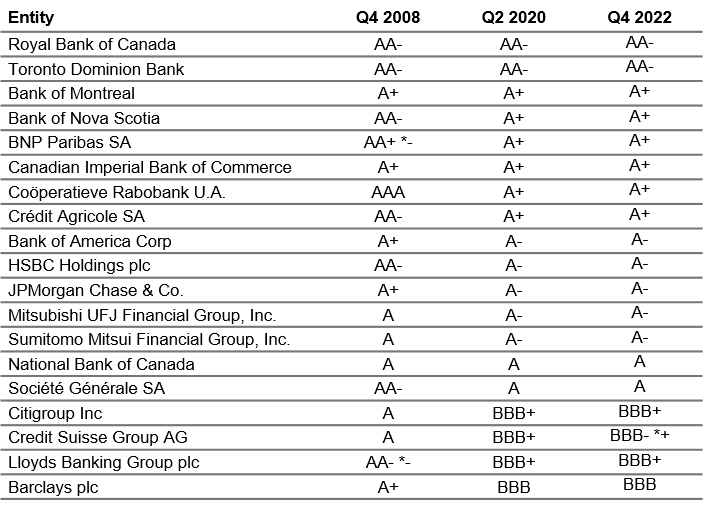

Bank Credit Rating Migration Concerns

As discussed, fears of a global recession for the latter half of 2023 would lead to an increase in the number of bank NPLs. This in turn will put downward pressure on the credit quality and on the public ratings of these banks. One of the most notable changes following the GFC was the deterioration of global bank ratings, with the global banking sector becoming an average single A rated sector, rather than the AA rated sector previously (Table 3). It is possible that over time we see a similar migration of credit ratings so that the global banking industry becomes on average rated even lower. Fears that this would come to pass during the Covid-19 crisis haven’t been realised, but the underlying reasons are worth examining as they haven’t lost their relavence.

At a very high level the possibility of bank credit migration should not necessarily be cause for concern as credit ratings are often viewed on a relative basis. In the years after the GFC single A became the new AA.

In addition to the pure focus on the ability of a bank to absorb losses, there is also the question of the impact on banks' ratings from that of the underlying sovereign. Rating agencies have different methodologies as to how sovereign ratings impact bank credit ratings and these have changed over time. However, using Moody’s as an example, the general rule is that banks cannot have a higher long term rating than the sovereign rating of the country in which they are domiciled (with a few exceptions) and although S&P do not have a direct link there are no examples of banks rating more than one notch higher than the sovereign rating. During the Covid-19 crisis, public debt levels around the world spiked, with UK debt (as a percentage of GDP) rising from 83.0% in 2020 to 103.7% in 2021, for instance. Economic growth has mitigated the need to confront this growing debt burden during 2020-2, but if the economy slows then this would be expected to impact sovereign credit ratings. Indeed, as Liz Truss found in late 2022, the ability and willingness of states to address rising public debt is being closely watched by markets, and when ignored can have severe consequences. Alongside this growing debt burden, comes the higher cost of servicing this debt, becoming particularly painful after a decade of ultra low rates. The cost of servicing the US government’s debt burden rose 40% from Q4 2021 to Q4 2022, while the US government’s debt rose only 4%. Any analysis of bank credit therefore needs to have a strong focus on sovereign ratings expectations particularly as when a financial or economic crisis occurs, the impact is often across the banking sector for a country as a whole rather than a specific bank.4. S&P Long Term Credit Rating

Source: Bloomberg, HSBC Asset Management

HSBC focus on Credit Migration

The broad credit migration of the banking sector is not something that we can control, but we can ensure that we have appropriate focus on those banks (and countries) where we feel that downgrades will either decrease liquidity or result in a rating that is lower than permitted for a rated money market fund.

Our credit matrix is a key driver of our investment process setting out limits per (parent) issuer based on our proprietary internal credit rating and ‘size category’, with lower ratings and smaller ‘size category’ translating into a reduced exposure and shorter maturity limit. This is particularly important when the focus of the investment and credit process is to avoid credit migration and defaults. This also enables us to more effectively manage our overall exposure to banks that have lower ratings. There is a strong focus on the contribution of these banks to our overall Weighted Average Life (WAL) so we can manage this combined exposure and better understand any potential impact on liquidity. Exposure to particular issuers with ratings just above the minimum A-1/P-1 are sized so that we do not become forced sellers in the result of a downgrade, as the fund rating agencies allow longer holding periods following downgrades for smaller exposures. In addition we ensure that these issuers are also shorter in maturity as this also allows more flexibility in managing exposure post a credit ratings downgrade. Our contribution to WAL focus also extends to countries so that we can easily gauge the possible impact of any stress within the banking sector of a particular country.The processes we have in place are already geared towards events such as managing the credit migration that we anticipate will occur in the future. Our internal credit rating assessment follows the individual credit evolution of each of our approved issuers. The result is a more proactive approach to credit which can lead to a reduction in the maturities allowed for specific issuers to more effectively manage risk. This had been the case with Credit Suisse, which both our credit analyst team and our portfolio management team followed closely for several years before its collapse in March 2023. For instance, in March 2021, in response to the Greensill and Archegos failures, our portfolio management team put Credit Suisse on hold for everything except overnight repo for four months due to concerns over governance and risk appetite. These worries were never fully dispelled, and in the lead up to the collapse itself Credit Suisse was steadily downgraded by our credit analyst team. From January 2022, it was downgraded from a B to a C, in August down to a D, and October we froze the limits entirely, several months in advance of their collapse and subsequent merger with UBS. This matrix system allows us to tune our exposure to an issuer, and conveys the credit research team’s level of conviction, as opposed to a binary rating. Our credit analyst and portfolio management teams investigate the banks all year round to ensure our portfolio minimises the risk of being exposed to the ‘slowest antelope’ in a crisis, as Credit Suisse proved to be.

Managing risk in this way can impact the yield, but the focus should remain firmly on credit migration rather than yield enhancement as we navigate the fallout from this crisis period and any further evolution it may take. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that holding downgraded bank issuance could have a significant effect on the shadow NAV and yield of the fund. We do not expect a broad-based downgrading of the banking sector, though the possibility remains for a more selective re-rating of some individual banks and some country banking sectors. Our credit assessment process should flag issues in advance and, even if the outcomes are worse than our expectations, our investment focus (as detailed above) will enable us to effectively manage them through a period of ratings changes.

Conclusion

It is too early to fully conclude the lessons that may have been learnt from the most recent crisis as the full impact has yet to be felt in economic data and possibly in financial markets. It is somewhat surprising that risk assets have rebounded so far and so quickly from the sell-off in mid-March and it seems inevitable that we will see setbacks and that markets will remain less liquid.

- Recent crises have rocked an increasingly fragile treasury market. There are structural reasons for this, including higher supply as US Government debt rises and lower demand as primary dealers’ role has diminished.

- Liquidity management has been key to navigating the current market environment and we continue to focus on this process

- Client concentration has been a key driver of redemptions across all money market funds

- The uncertainty around the outlook for corporates mean we remain extremely cautious about investing in these issuers, particularly in certain sectors

- High quality banks remain the focus of our investment strategy and we firmly believe that we will not see defaults in that segment of the banking sector

- Credit migration, with possible bank and sovereign downgrades, will be a key theme in the medium term, but we do not expect a major re-rating of the global banking sector

- Our robust global investment process and focus is well tailored toward dealing with any bank credit migration

What should I do if I still have questions?

Please don’t hesitate to contact your Liquidity sales specialist.

|

Americas T: +1 (1) 212 525 5750 |

EMEA T: +44 (0) 20 7991 0406 |

France T: +33 1 58 13 15 26 |

|

Germany T: +49 (0) 211 910 4784 |

Asia T: +852 2284 1376 |

Japan T: +813 3548 5634 |

|

Switzerland T: +41 44 206 2600 |

UK Corporates T: +44 (0) 20 7991 7153 |

UK Financial Institutions T: +44 (0) 7796 693 275 |

What are the key risks?

The value of investments and any income from them can go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amount originally invested.

- Asset backed securities (ABS) and mortgage backed securities (MBS) risk. ABS and MBS typically carry prepayment risk, as well as having potential for default. The securities can carry an above-average risk of being hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price

- Counterparty risk. The possibility that the counterparty to a transaction may be unwilling or unable to meet its obligations

- Credit risk. A bond or money market security could lose value if the issuer’s financial health deteriorates

- Derivatives risk. Derivatives can behave unexpectedly. The pricing and volatility of many derivatives may diverge from strictly reflecting the pricing or volatility of their underlying reference(s), instrument or asset

- Exchange rate risk. Changes in currency exchange rates could reduce or increase investment gains or investment losses, in some cases significantly

- Investment leverage risk. Investment leverage occurs when the economic exposure is greater than the amount invested, such as when derivatives are used. A Fund that employs leverage may experience greater gains and/or losses due to the amplification effect from a movement in the price of the reference source

- Liquidity risk. Liquidity risk is the risk that a Fund may encounter difficulties meeting its obligations in respect of financial liabilities that are settled by delivering cash or other financial assets, thereby compromising existing or remaining investors

- Money Market Fund risk. The fund's objective may not be achieved in adverse market conditions. During times of very low interest rates, the interest received by the Fund could be less than the costs of operating the Fund

- Operational risk. Operational risks may subject the Fund to errors affecting transactions, valuation, accounting, and financial reporting, among other things

Important information

For Professional Clients only and should not be distributed to or relied upon by Retail Clients.

The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. Past performance contained in this document is not a reliable indicator of future performance whilst any forecasts, projections and simulations contained herein should not be relied upon as an indication of future results. Where overseas investments are held the rate of currency exchange may cause the value of such investments to go down as well as up. Investments in emerging markets are by their nature higher risk and potentially more volatile than those inherent in some established markets. Economies in Emerging Markets generally are heavily dependent upon international trade and, accordingly, have been and may continue to be affected adversely by trade barriers, exchange controls, managed adjustments in relative currency values and other protectionist measures imposed or negotiated by the countries with which they trade. These economies also have been and may continue to be affected adversely by economic conditions in the countries in which they trade. Mutual fund investments are subject to market risks, read all scheme related documents carefully.

The material contained herein is for information only and does not constitute legal, tax or investment advice or a recommendation to any reader of this material to buy or sell investments. You must not, therefore, rely on the content of this document when making any investment decisions. This document is not intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation. This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe to any investment. Any views expressed were held at the time of preparation, reflected our understanding of the regulatory environment; and are subject to change without notice.

The funds mentioned in this document are sub-funds of HSBC Global Liquidity Funds plc, is an open-ended Investment company with variable capital and segregated liability between sub-funds, which is incorporated under the laws of Ireland and authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland. The company is constituted as an umbrella fund, with segregated liability between sub-funds. UK based investors in HSBC Global Liquidity Funds plc are advised that they may not be afforded some of the protections conveyed by the provisions of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. The Company is recognised in the United Kingdom by the Financial Conduct Authority under section 264 of the Act. The shares in HSBC Global Liquidity Funds plc have not been and will not be publicly offered for sale in the United States of America, its territories or possessions and all areas subject to its jurisdiction, or to United States Persons. All applications are made on the basis of the current HSBC Global Liquidity Funds plc Prospectus, Key Investor Information Document, Supplementary Information Document (SID) and most recent annual and semi-annual reports, which can be obtained upon request free of charge from HSBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited, 8 Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London, E14 5HQ. UK, or the local distributors. Investors and potential investors should read and note the risk warnings in the prospectus and relevant KIID and additionally, in the case of retail clients, the information contained in the supporting SID. It is important to remember that there is no guarantee that a stable net asset value will be maintained.

HSBC Global Liquidity Funds are Money Market Funds (MMF) and therefore:

a. are not a guaranteed investment

b. are different from an investment in deposits and there is a risk that the principal invested in an MMF may fluctuate;

c. do not rely on external support for guaranteeing the liquidity of the MMF or stabilising the NAV per unit or share;

d. the risk of loss of the principal is borne by the investor

The MMF have availed of the derogation provided for under Article 17(7) of the Money Market Fund Regulation and accordingly a Fund may, in accordance with the principle of risk-spreading, invest up to 100 per cent of its assets in different money market instruments issued or guaranteed separately or jointly by the European Union, the national, regional and local administrations or their central banks, the European Central Bank, the European Investment Bank, the European Investment Fund, the European Stability Mechanism, the European Financial Stability Facility, a central authority or central bank of a third country, the International Monetary Fund, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Council of Europe Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Bank for International Settlements, or any other relevant international financial institution or organisation to which one or more member states of the European Union belong.

HSBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited provides information to Institutions, Professional Advisers and their clients on the investment products and services of the HSBC Group. Approved for issue in the UK by HSBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited, who are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

www.assetmanagement.hsbc.com/uk

Copyright © HSBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited 2020. All rights reserved.

I-1098. Expiry 31/12/2020