Multi-Asset Insights

In a nutshell

- Gold’s role in portfolios is shifting from a tactical hedge against inflation or falling real yields to a structural reserve asset, as its price has risen sharply even in an environment of high real rates and subdued inflation

- Central banks, especially in emerging markets, have become the dominant marginal buyers of gold, accumulating it for reserve credibility and geopolitical reasons, which tightens tradable supply and creates a structural price floor

- This regime change reduces gold’s sensitivity to traditional drivers such as real yields and positions it as a hedge against monetary debasement, fiscal dominance, and the gradual erosion of major currencies’ purchasing power

- Rising sovereign debt, shifting policy priorities, and geopolitical fragmentation weaken the hedging power of government bonds and currencies, increasing the relevance of gold as a diversifier against credibility and balance-sheet risks

- Strategic asset allocation frameworks may need to evolve, treating gold as a long-term reserve allocation rather than a small, tactical position, with selective exposure to gold miners offering additional diversification and growth potential

The shifting role of gold

For decades, gold had a narrowly defined role in portfolios of a tactical hedge that outperformed during rising inflation or falling real yields. That role is now changing.

Historically, gold occupied a narrowly defined role. It was treated as a tactical hedge against inflation surprises or a beneficiary of falling real yields, valuable primarily during specific macro regimes and dispensable outside them. When real rates rose or inflation moderated, gold’s opportunity cost increased, and its relevance diminished. This framework shaped asset allocation decisions for decades and reinforced the perception of gold as an episodic, event-driven exposure rather than a structural allocation.

However, gold’s break to successive all-time highs in January 2026, followed by a sharp late-month correction, has further challenged the long-held assumptions about how the asset should behave. Over the past year, gold prices have risen materially alongside risk assets, even as real yields remained high, and inflation momentum subdued.

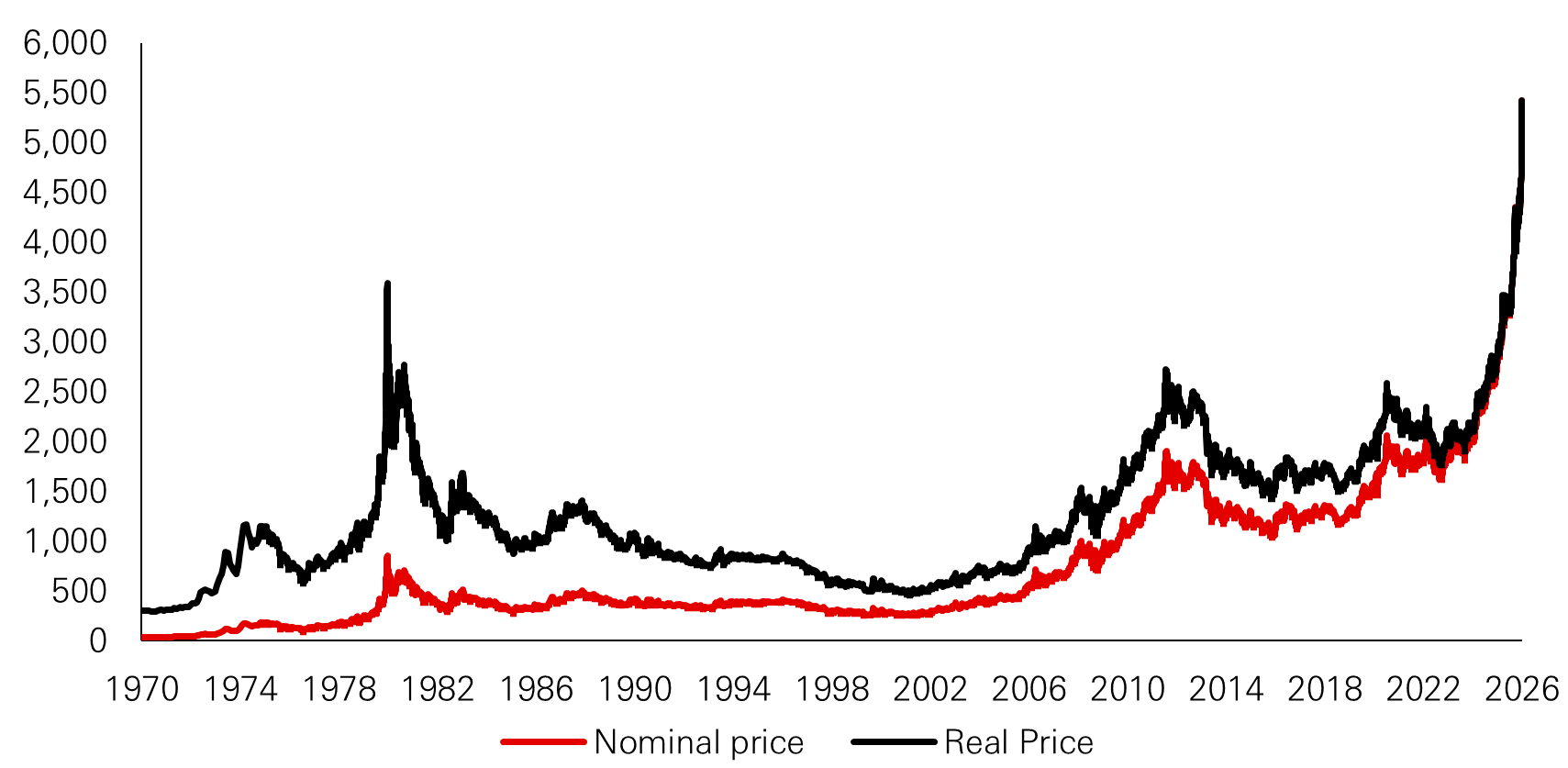

Figure 1: Gold price (USD/oz)

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of February 2026.

This unusual coexistence has raised questions about whether the drivers of gold have fundamentally shifted, and whether there is a need to rethink the asset’s standing in long-term strategic allocations. The subsequent pullback after the January peak has reinforced that gold remains volatile in the short term, but with prices having risen more than 65 per cent during 2025 and central banks’ increasing share of global gold reserves, it is clear that gold can no longer be evaluated solely through a cyclical lens.

A structural change in the marginal buyer

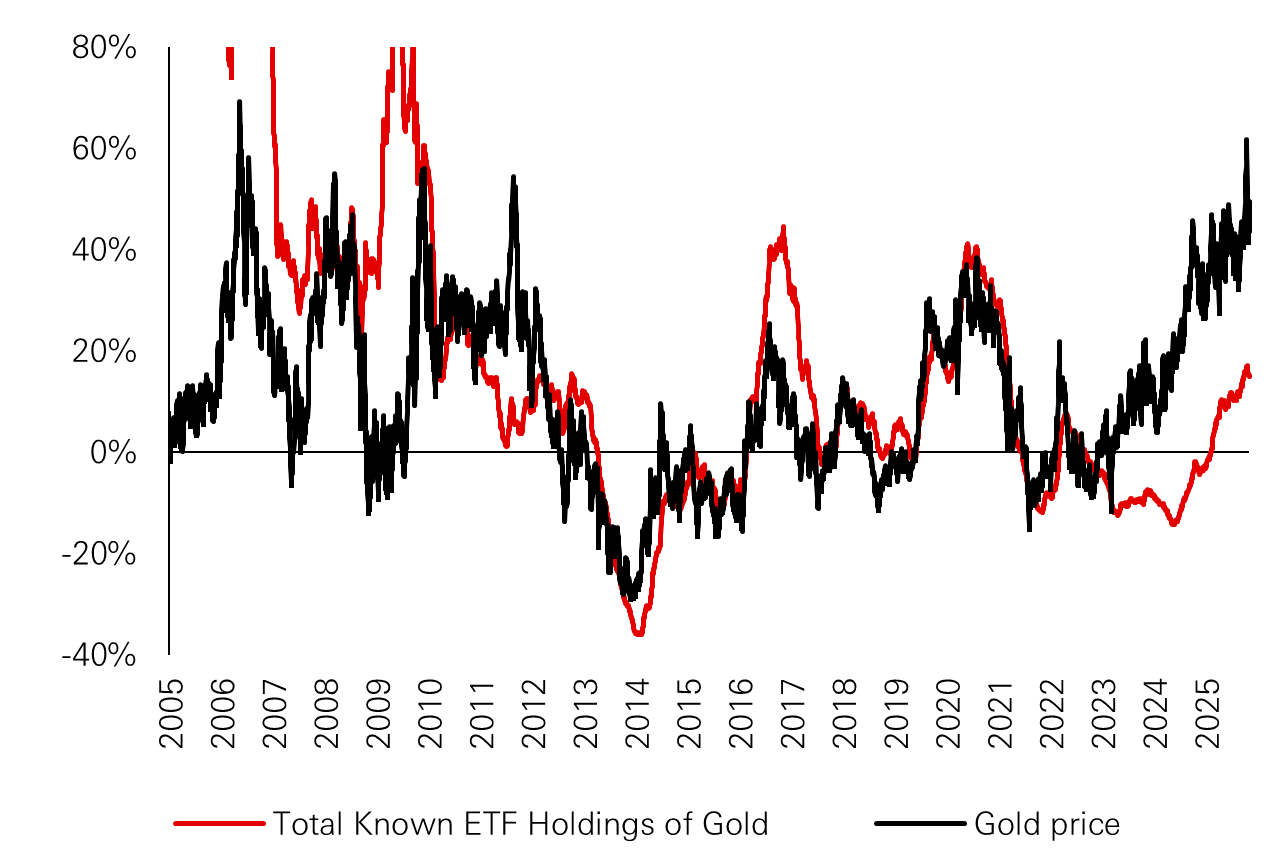

The shift begins with the changing profile of gold’s dominant buyer. Historically, gold prices were driven largely by private-sector flows, particularly ETFs and futures positioning, which made gold highly sensitive to real yields, dollar strength, and tactical risk sentiment. In fact, ETF inflows were a reliable proxy for investor demand and price direction which is evident in the in-sync movement of ETF holdings and gold prices, exhibiting a correlation of roughly 60 per cent until 2023.

However, that relationship has weakened materially. In 2023, despite the rally, ETF holdings experienced liquidation, and only resumed inflows in February 2025 when gold prices had already crossed the $2,700 mark. The divergence is even more prominent when looked at since 2020, with gold up nearly 100 per cent while ETF holdings down by roughly 12 per cent. This break underscored that traditional investment flows – ETF positioning and private-sector hedging – have become secondary to persistent purchases from central banks, particularly in emerging markets.

Figure 2: ETF holdings of gold versus gold price

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of November 2025.

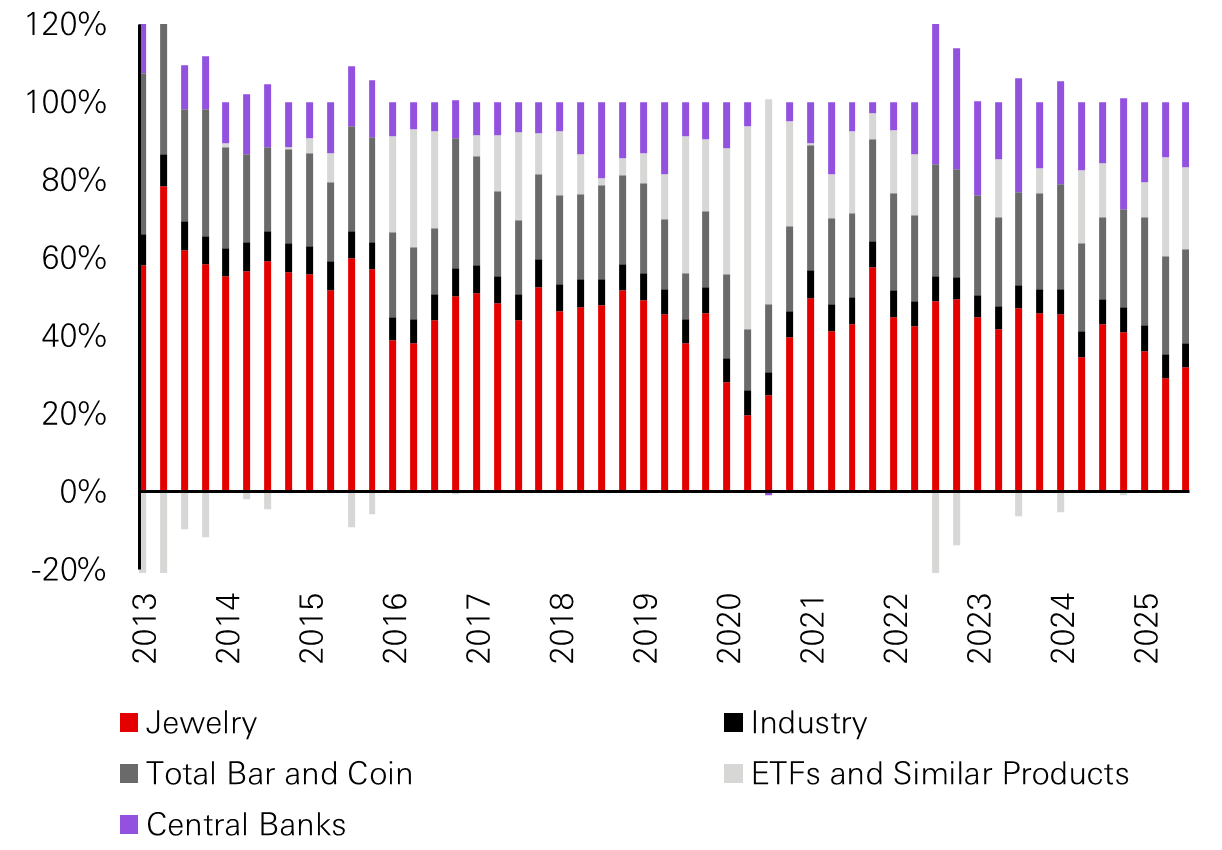

Figure 3: Share of gold demand

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of November 2025.

These sovereign entities are not responding to headline CPI prints or relative interest-rate moves. They are accumulating it for strategic reasons tied to reserve credibility concerns, geopolitical fragmentation, and vulnerabilities associated with holding reserves in foreign jurisdictions. As geopolitical blocs grow increasingly wary of sanctions risk, custody restrictions, dollar settlement dependencies, or discretionary policy actions by large reserve-currency issuers, gold has re-emerged as the only large-scale reserve asset independent of political architecture. As a result, gold demand is not just rising in absolute terms but changing the composition of global reserves. Previously, reserve diversification meant holding different currencies within the same fiat system. Now, diversification increasingly means moving outside the fiat system altogether.

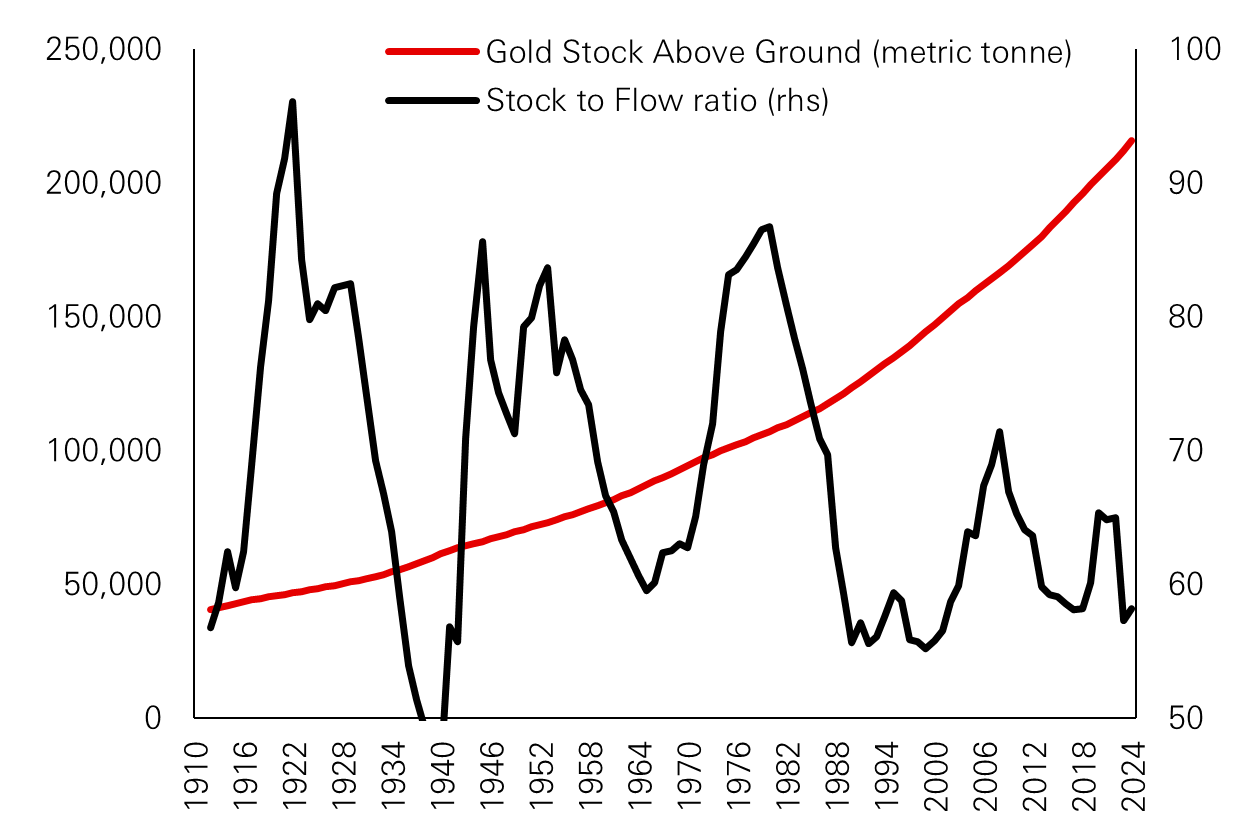

This distinction matters. When gold’s marginal buyer is a private investor, demand fluctuates with inflation expectations, monetary policy cycles, and relative yields. When the marginal buyer becomes a central bank, which does not respond to price signals, the asset ceases to behave like a cyclical trade. Instead, it begins to resemble a reserve asset with constrained supply and limited float. Gold is experiencing this structural change with the central banks now holding roughly a quarter of global gold reserves, a level that fundamentally alters the market’s stock-flow dynamics.

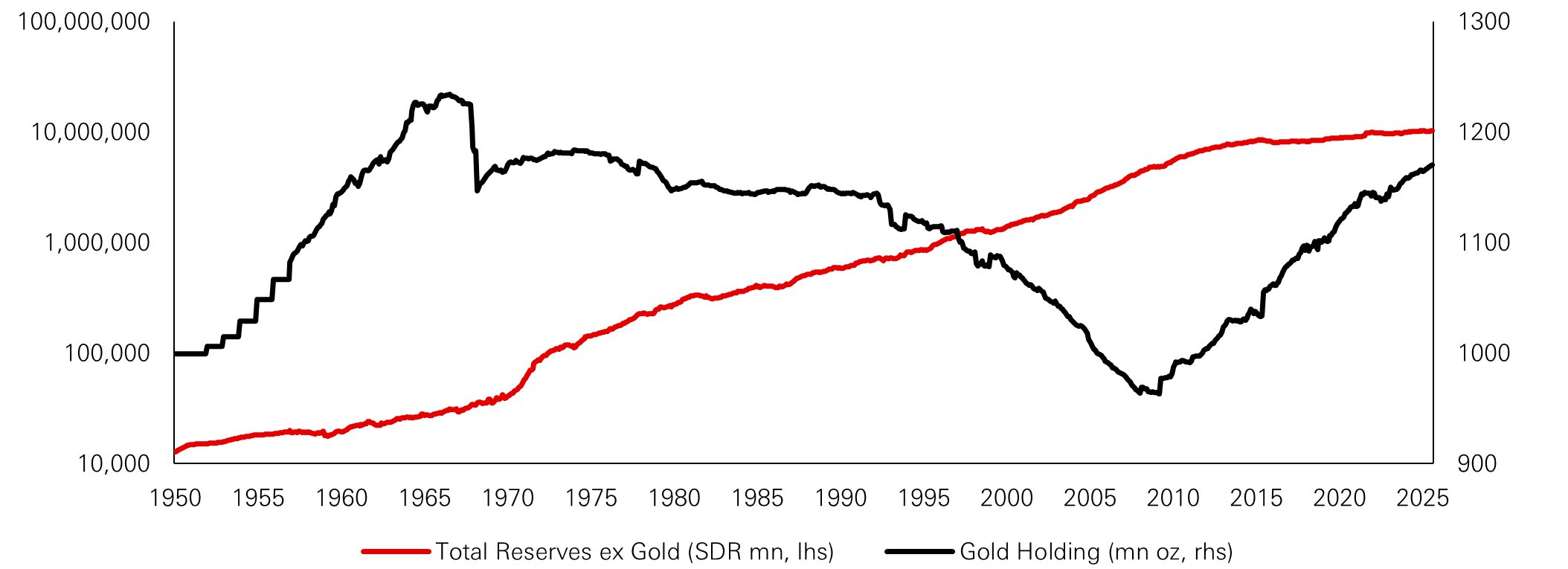

Figure 4: IMF world reserves ex gold versus gold reserves

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of November 2025.

From yield sensitivity to stock-flow dominance

Unlike commodities where supply can respond elastically to price, gold mine output adjusts only slowly, meaning sustained accumulation directly tightens available liquidity. This shift helps explain why gold has performed strongly even as real yields remained elevated. Gold is no longer priced primarily on opportunity cost. It is increasingly priced on balance-sheet demand. When reserve managers accumulate gold, they do so irrespective of short-term carry considerations. Central bank accumulation, thus, removes tradable supply from a market not structured to replenish it quickly. The result is gold beginning to trade like a finite reserve with limited float, rather than a commodity with cyclical elasticity.

Figure 5: Gold stock and flow

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 6: Gold stock growth

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of November 2025.

In this regime, gold develops a structural price floor. That floor is not anchored to inflation expectations or Fed policy alone, but to the ongoing withdrawal of supply from tradable markets. As long as central banks continue to accumulate, a behaviour driven by long-term geopolitical incentives rather than cyclical conditions, gold’s downside becomes more limited than historical models would imply. Hence, traditional frameworks that evaluate gold purely through real-rate regressions are bound to increasingly misprice its risk-return profile.

Moreover, as the US could enter a capex-heavy industrial investment cycle and embraces tariff-dependent fiscal expansion, concerns around medium-term inflation persistence and debt sustainability remain alive, even if headline inflation moderates. Fed rate cuts in this environment do lower the explicit opportunity cost of holding gold, but they operate atop a structural floor already set by central-bank accumulation. The result is an asymmetry i.e. cyclical conditions accelerating gold’s upside, but they are not required to justify its price level.

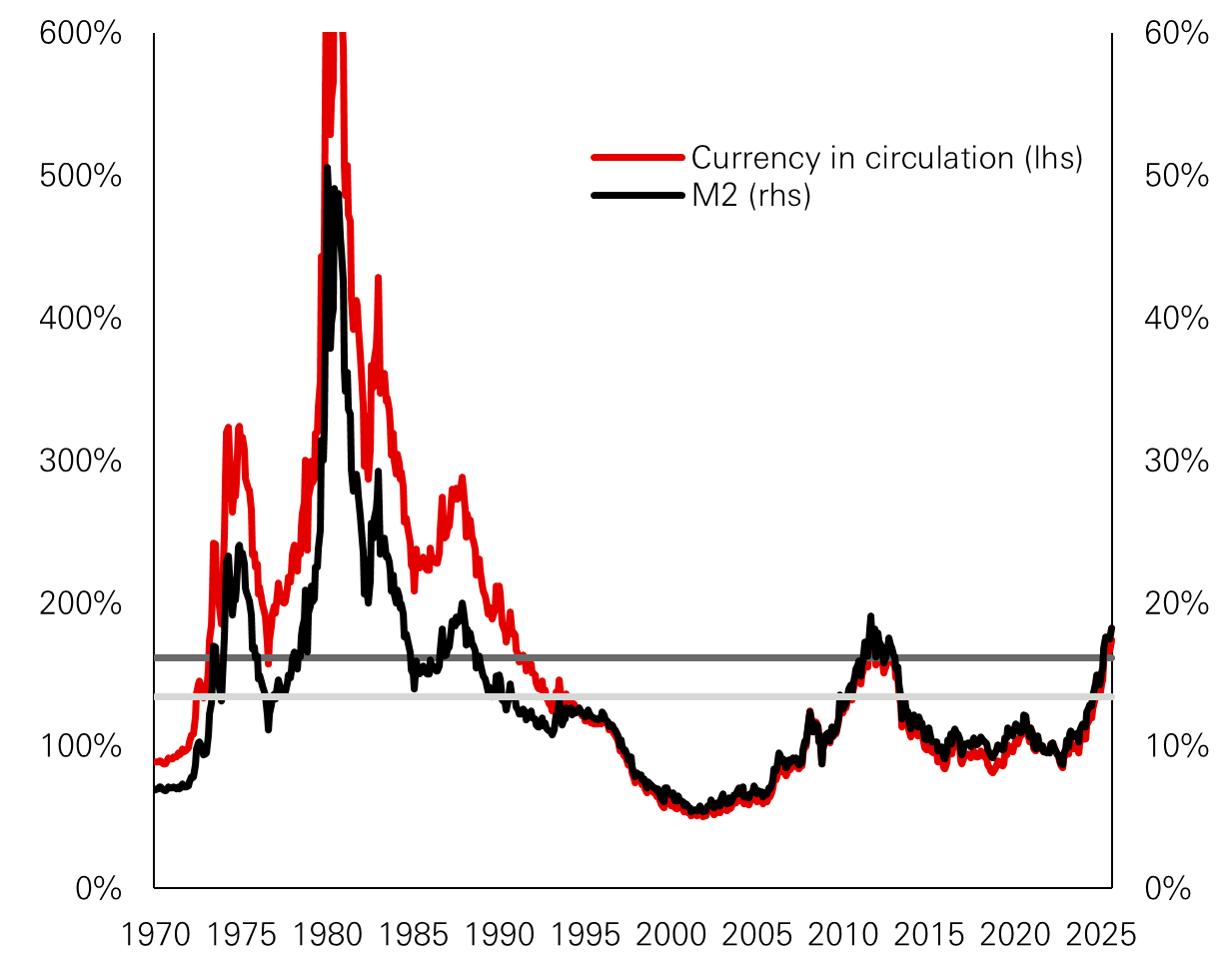

Gold’s all-time high: A feature of regime change

Gold trading at or near all-time highs naturally raises concerns about forward-looking returns. The January 2026 peak, followed by a swift correction, has reinforced this tension between structural strength and tactical vulnerability. Historically, however, gold’s strongest multi-year performance has often followed prior peaks rather than preceded reversals. All-time highs in gold have tended to coincide with periods of regime transition, not cyclical exhaustion.

In the early 1970s, gold broke to new highs as the Bretton Woods system collapsed and fiat currency regimes emerged. Prices continued to rise for nearly a decade as inflation volatility, fiscal expansion and currency debasement became embedded features of the macro environment. Similarly, gold reached new highs in 2011 amid the eurozone sovereign crisis and aggressive post-GFC monetary expansion. While prices subsequently consolidated, they did so within a higher structural range, rather than reverting to pre-crisis levels.

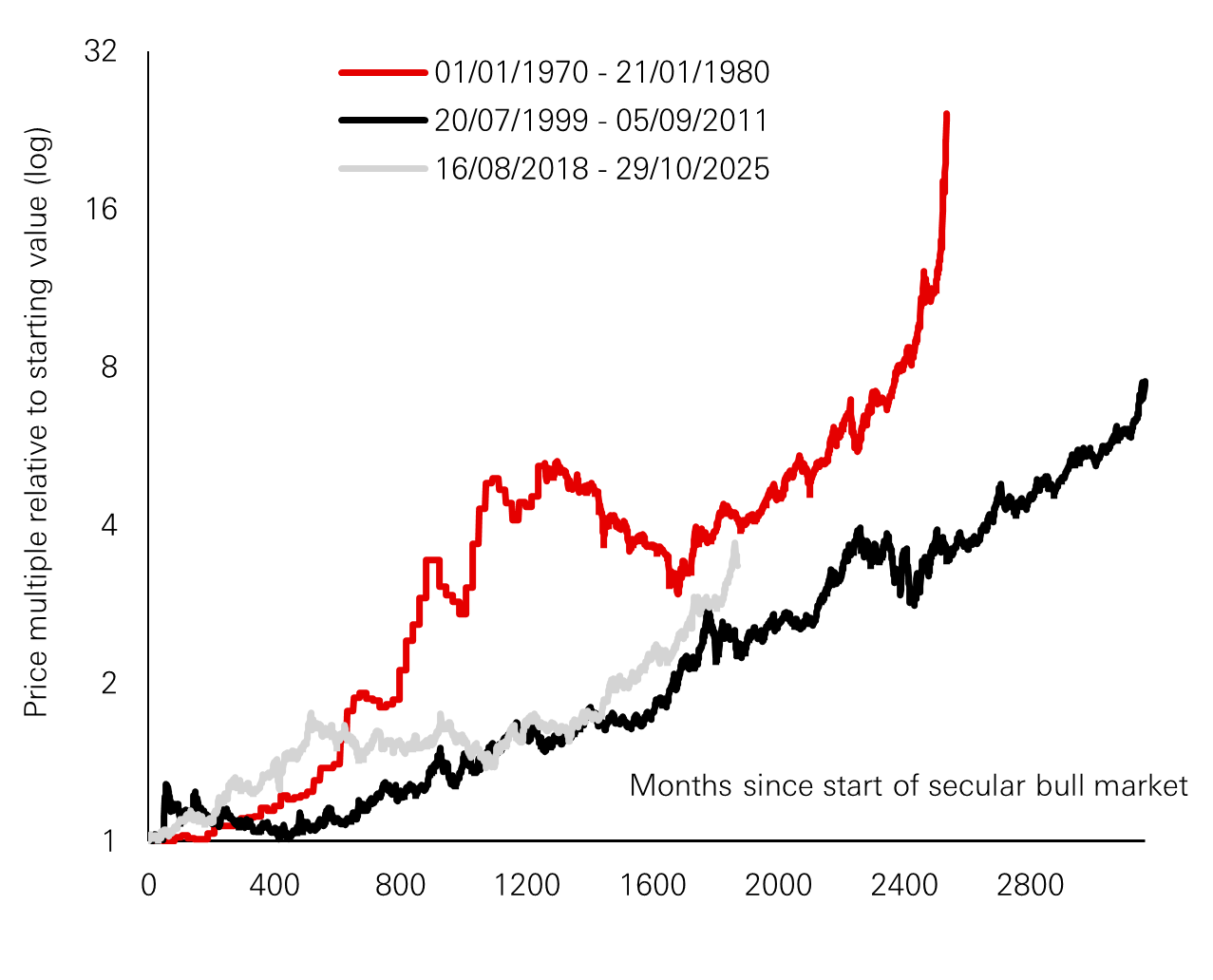

Figure 7: IMF world gold reserve as a share of US money

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 8: Gold secular bull markets

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Source: HSBC AM. Data as of September 2025.

What matters in these episodes is not the nominal price level, but the macro regime in which those highs occur. Gold tends to peak cyclically only when real rates rise decisively, fiscal discipline is restored, and confidence in monetary credibility strengthens. None of those conditions are currently present. Instead, today’s environment is characterised by persistent fiscal expansion, higher equilibrium inflation volatility, and geopolitical fragmentation – features that historically coincide with prolonged gold bull markets rather than short-lived price spikes.

Viewed through this lens, current price levels are less a signal of excess and more an indication that markets are repricing gold’s role within a structurally different system. All-time highs, in this context, reflect a reset in gold’s function rather than a speculative overshoot.

Gold and dollar’s eroding purchasing power

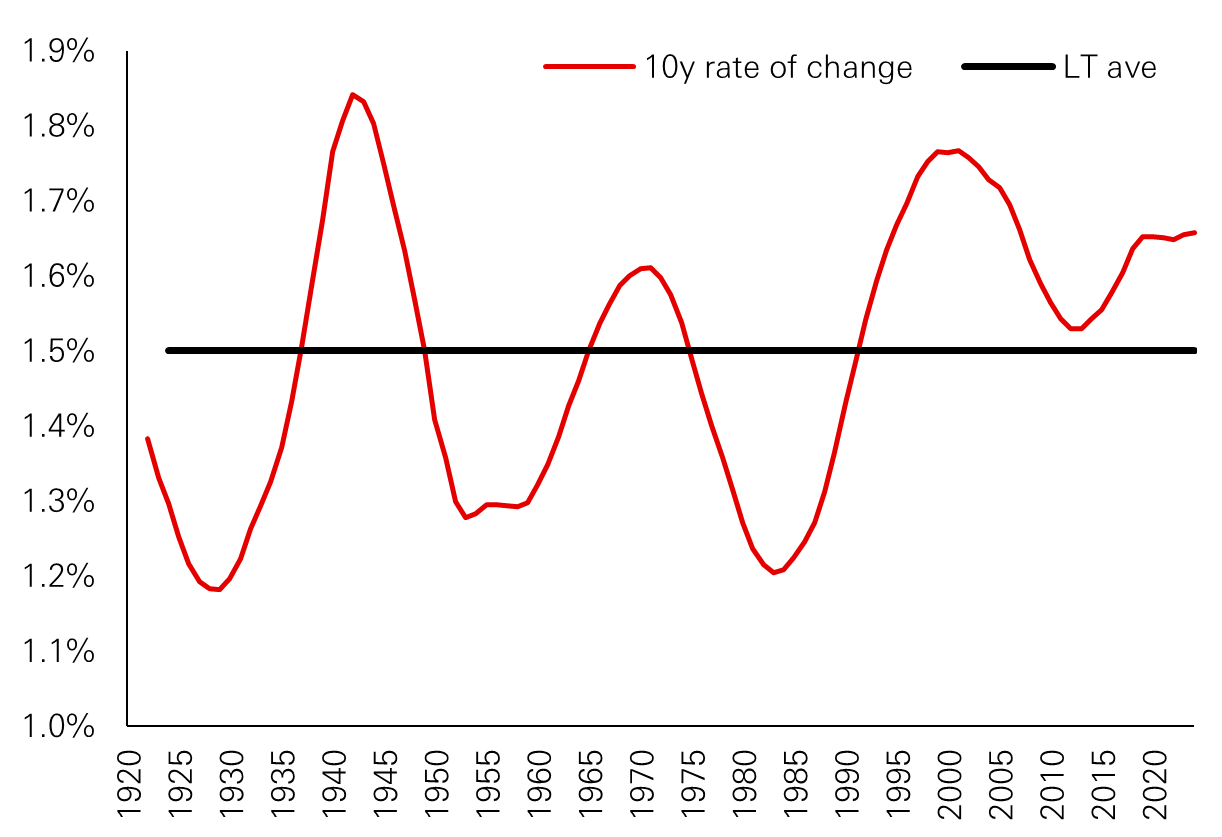

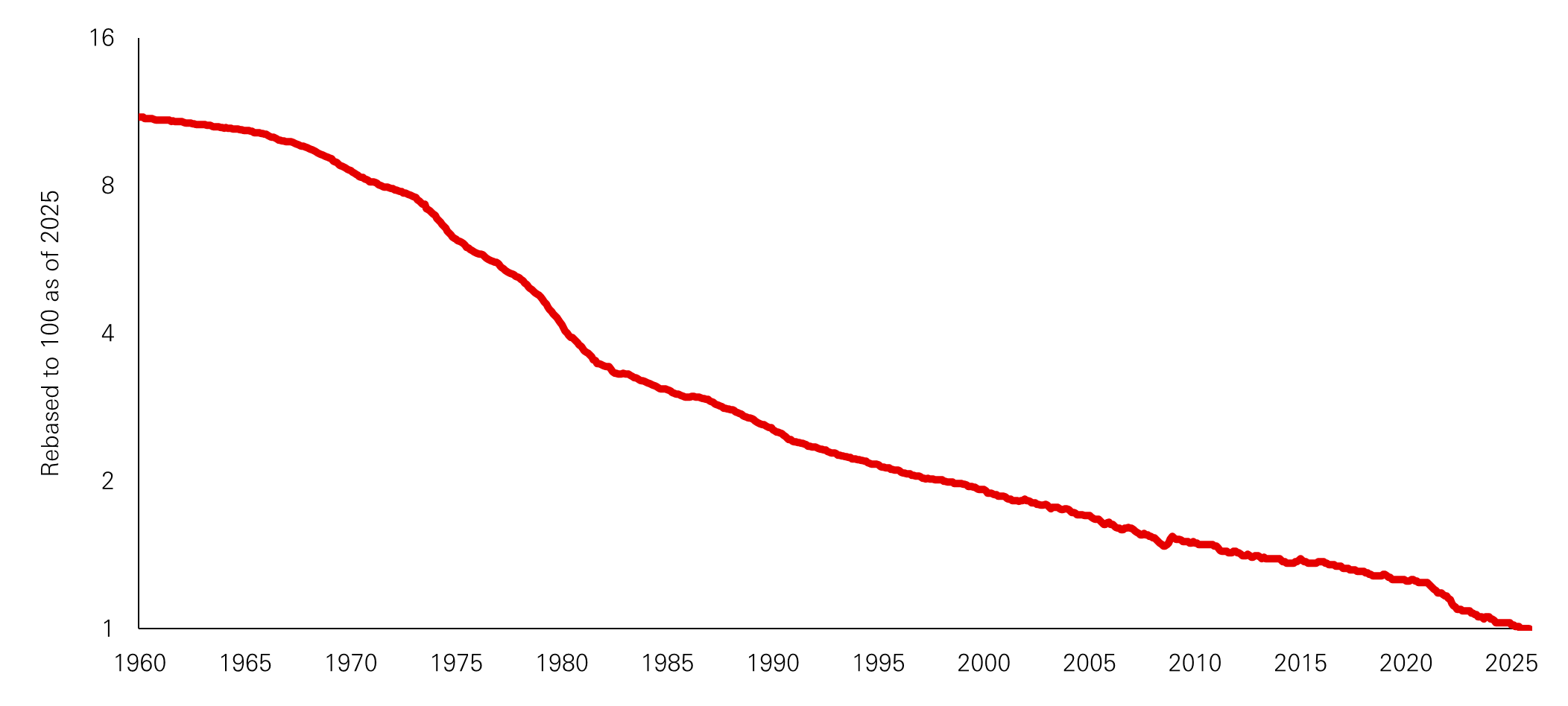

Another critical, and often underappreciated, driver of gold’s long-term performance is its relationship to the purchasing power of fiat currencies, particularly the US dollar. While gold is frequently analysed against nominal interest rates or inflation prints, its most consistent long-run relationship is with the cumulative erosion of real purchasing power.

Since the early 1970s, the US dollar has lost over 85 per cent of its purchasing power. Over the same period, gold has preserved real value by acting as a long-duration hedge against monetary debasement rather than short-term inflation volatility. Importantly, this relationship does not require inflation to be persistently high; it only requires that inflation exceeds the credibility and discipline of monetary and fiscal frameworks over time.

Figure 9: US dollar purchasing power

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of November 2025.

The current cycle reinforces this dynamic. Even as headline inflation has moderated from post-pandemic peaks, structural forces imply sustained pressure on fiscal balances. In such an environment, policymakers face an implicit trade-off between growth stability and currency purchasing power. Historically, this trade-off has favoured nominal stability over real value preservation.

Gold benefits from this asymmetry. It does not need inflation to accelerate sharply to perform; it only needs monetary regimes to tolerate gradual erosion of real value. This makes gold less a hedge against inflation surprises and more a hedge against policy credibility drift. When currencies weaken slowly but persistently, gold compounds quietly rather than spiking episodically. Hence, gold’s relevance lies in preserving purchasing power across decades when fiscal and monetary discipline is structurally challenged.

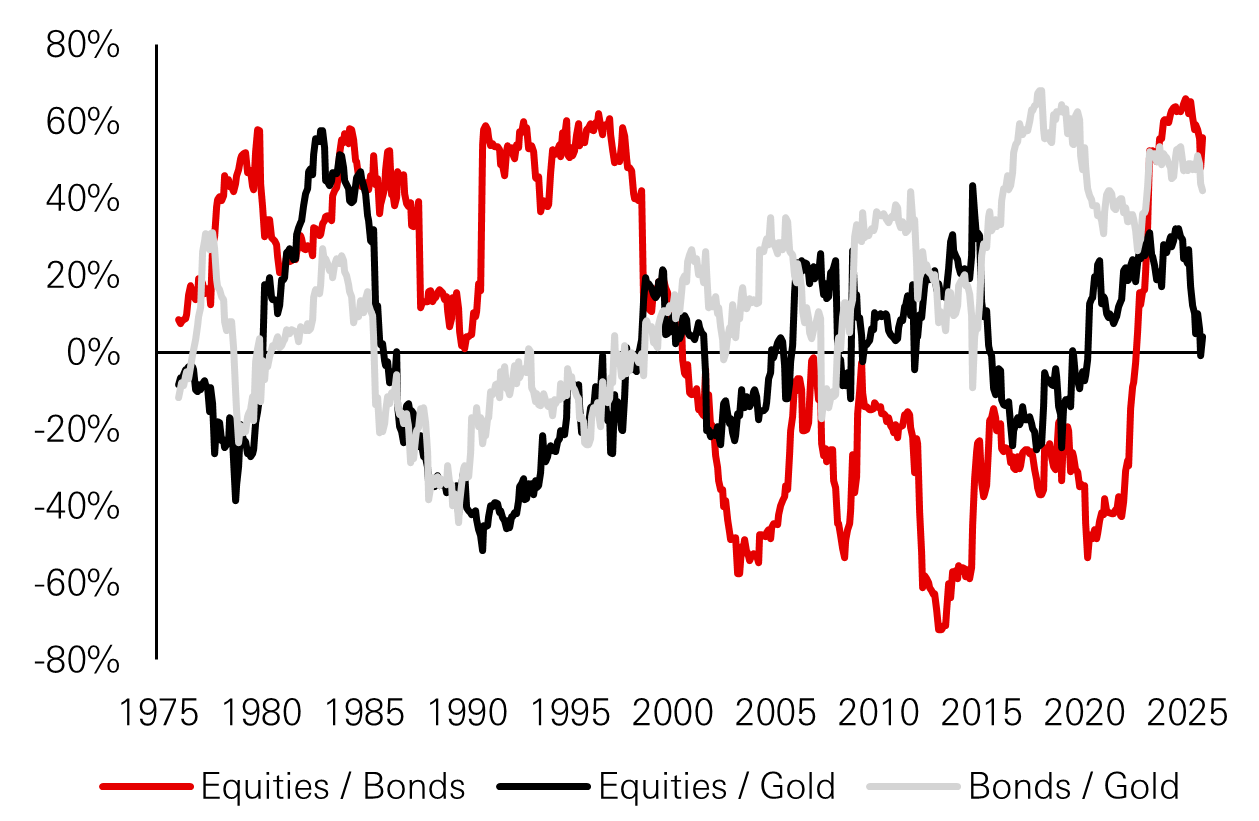

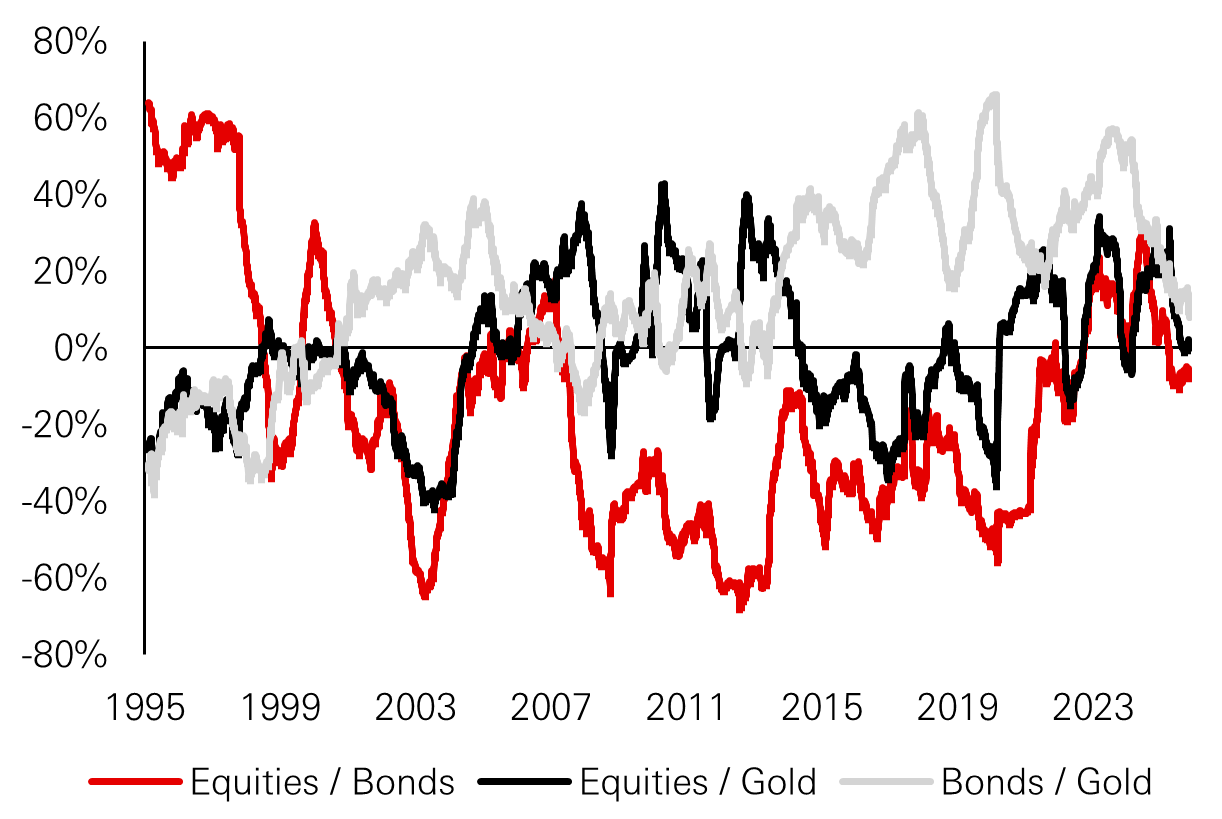

Shifts in correlation with risk assets

One more factor that is changing its nature now is the sovereign risk. In prior decades, government bonds served as the ultimate hedge against economic downturns. Today, high and rising debt burdens, ageing demographics, rearmament spending, industrial policy and climate-transition capex are placing sustained pressure on public finances across developed markets.

In such an environment, sovereign bonds hedge growth risk but increasingly fail to hedge fiscal credibility risk. Currency hedges mitigate FX volatility but do not address reserve concentration or financial weaponisation. Cash hedges rate volatility but not debasement or real-value erosion. Gold uniquely hedges all three simultaneously because it has no issuer, no counterparty, and no jurisdictional dependency.

Figure 10: Rolling 3-year monthly correlations

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 11: Rolling 12-month daily correlations

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of November 2025.

This is why gold’s recent correlation with risk assets should not be misinterpreted. Traditional intuition holds that if gold rallies alongside equities, it is being driven by speculative sentiment rather than portfolio hedging. In reality, the co-movement reflects investors hedging credibility risk, not macro downturn risk. Currently, equities are benefiting from AI-driven capital deepening, resilient earnings and liquidity-accommodating policy signals. Gold, meanwhile, is being accumulated against a different set of risks. Hence, the simultaneous rise in both assets should not be read as behavioural exuberance; it reflects an asset-allocation environment where economic growth expectations and institutional distrust coexist.

Investment implications and conclusion

Gold’s rapid appreciation into early 2026 has naturally introduced near-term volatility, and the sharp pullback following January’s record highs illustrates that consolidation phases are likely to be a recurring feature of this regime. Fed rate cuts reduce the explicit opportunity cost of holding gold, but they operate on top of a much larger structural demand base that is unlikely to reverse.

This asymmetry is important. Cyclical factors may accelerate or decelerate gold’s price action, but they are no longer prerequisites for its performance. Even after corrections from elevated levels, the structural motivations for gold accumulation remain intact as long as geopolitical fragmentation, reserve diversification, and fiscal dominance persist.

While portfolio construction has not fully internalised this transition, the implications are clear. If gold now hedges structural risks rather than cyclical ones, allocation sizing must reflect that reality. A small, tactical exposure calibrated to inflation surprises is insufficient in a world where gold’s primary function is to hedge reserve credibility and sovereign balance-sheet risk.

This does not imply abandoning tactical discipline. Rather, it suggests reframing gold as a strategic reserve asset within portfolios — one that complements, rather than replaces, traditional diversifiers. Gold does not compete with equities for growth exposure, nor with bonds for income. Instead, it provides resilience against the erosion of trust in sovereign issuers whose balance sheets are becoming structurally larger, older, and more politicised.

Additionally, exposure to gold miners could support portfolio diversification and growth. Despite the rally in gold prices, valuations of gold mining stocks remain below historical averages, with production costs maintained significantly lower than current gold prices. The combination of elevated gold prices and restrained equity valuations offers asymmetric upside if prices remain structurally supported.

Overall, in a multipolar world defined by competing power blocs, persistent debt expansion, and structurally volatile inflation, gold functions not as a cyclical trade but as a strategic reserve asset embedded within long-horizon portfolio construction – even as tactical corrections punctuate its structural ascent.